Joel Greenblatt's Greatest Investment

How a deli manager inspired Greenblatt to start Value Investors Club.

It’s August 1999.

The dot com bubble is in full swing. It’s a new investing world. Earnings are out, eyeballs are in. Investors care about servers, not sales.

Joel Greenblatt sits alone in his New York City office. He was already a legend. Greenblatt started Gotham Capital in 1985 with a $7MM check from “junk bond king” Michael Milken. From there he earned 50% per year for a decade. In 1994, having become sufficiently rich, he decided to return outside capital and focus on managing his own money.

Greenblatt was as perplexed as any value investor by the scene that lay in front of him. Markets were ripping to unsustainable heights. There wasn’t a whole lot to do. Pets.com, Amazon.com, Yahoo, Cisco and hundreds of other companies were bid higher and higher. The Nasdaq Composite Index would peak at 5,048 in just a few short months. It wouldn’t reach that level again for 15 years.

Meanwhile, somewhere in an undisclosed supermarket, a deli employee hangs up his apron after a long shift. It’s a Monday, and the deli man heads home. He fires up his new computer. It’s the first computer he’s ever owned - gifted to him by a family member. The deli man, a long time stock enthusiast and skilled investor, logs onto a Yahoo message board and writes a series of posts. He’s honed in on an obscure bank with an even more obscure capital structure. The deli man believes that this particular bank may be the best value of its kind in the United States.

Back to New York. Greenblatt and his partners think they’ve uncovered something unique. A little bank in New Jersey had just IPO’d. Greenblatt and his partners worked out the complex capital structure and saw what they thought was a great deal. Seemingly no other investor had pieced together the story. That’s when one of Greenblatt’s partners stumbles upon a Yahoo message board and sees posts from the deli man. They realize they’re not alone. Someone else is on the trail. It must be some other sophisticated hedge fund manager? Maybe a banking expert?

Greenblatt contacts this mystery poster and learns that he’s no billion dollar asset manager. He’s a supermarket employee. Some guy who cuts meat during the day and reads obscure financial filings at night. The light bulb goes off.

Greenblatt has been sitting in stuffy offices with Ivy league grads for the last 20 years. He’s run across the same people who think the same way. They went to the same schools and worked at the same funds. And someone outside his circle, a deli manager no less, has put together this profitable puzzle. If the deli man could do it, there must be others out there too.

Greenblatt ponders to himself. What if there was a place where likeminded investors could share their thoughts? What if this place was based on merit and nothing else? The internet was going to connect the world. What if Greenblatt could build a home for intelligent investors to discuss their favorite stocks? If only there were a club…

In the words of Paul Harvey - “Now you know the rest of the story”.

Hudson City Bancorp, Inc.

Greenblatt and the deli man owned Hudson City Bancorp, a New Jersey bank founded in 1868. Hudson City was originally a mutual bank that was going through a two step conversion to become a publicly traded entity.

Mutual Conversions

If you don’t know what a mutual conversion is, keep reading this section. If you are already aware, move on to the next section.

A mutual bank is one that is owned by its depositors. Kind of like a co-op. A mutual bank doesn’t have outside shareholders. The idea is that the bank would serve its customers, not profit off of them.

Anyway, a mutual conversion is the process by which a mutual bank becomes a traditional bank (one with shareholders). Depositors are given the opportunity to buy shares. Some mutuals go through a standard conversion, while others go through a two-step conversion.

A standard conversion is simple - depositors put up money to buy shares in the newly converted bank. Now depositors become shareholders in a more traditional sense.

A two step conversion is a bit more complicated. In a two-step conversion, the bank agrees to transfer partial ownership into a traditional stock corporation at IPO. Step one involves depositors buying shares in the new bank, just as in a standard conversion. But the remaining stock not owned by shareholders, is held in a mutual holding company (MHC). Within a few years of IPO, step two occurs, and the MHC sells off its remaining interest.

It’s important to note that in the second step conversion, the original shareholders (depositors and outsiders that purchase equity in step one of the conversion) will not be diluted. When the second step occurs, outside capital is used to purchase the MHC interest. That capital is simply added to the balance sheet. This is possible because the MHC isn’t an owner in the traditional sense. In effect, the MHC ownership acts more like treasury shares. It’s remnant mutual equity. When it converts to traditional stock, it’s simply sold to new investors. There is no dilution to prior shareholders. If you’re new to this concept, it can be a bit tricky. Here’s a good primer on the conversion process:

Anatomy of a Second-Step Conversion

Basically, shareholders at the time of IPO (or shortly thereafter) would have ownership in the business. When the second step happens a few years later, cash would come onto the balance sheet without any dilution to you as a shareholder.

To give an imperfect metaphor, it would look something like this. You and your rich friend John are partners in a business. You own half, and John owns half. John says he wants to sell his half of the business. He’s going to sell to Larry. Larry pays cash to buy out John. The deal is done. Except as John is walking out the door he says “Hell, I’m already rich, you guys take my sales proceeds as a gift and stick it back in the business.” Now, you still own your half, Larry owns half, and John’s money is thrown back onto the balance sheet. Except John doesn’t own anything. To you, this is found money.

Situation Overview

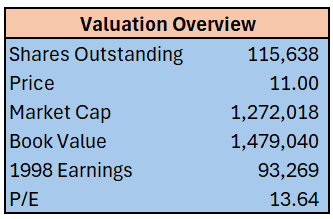

In August 1999, when Greenblatt and the deli man crossed paths, Hudson City had just completed the first step of its mutual conversion. Hudson IPO’d, selling 47% of the bank to depositors/public investors. Shares were valued at ~$11 on the public market shortly after IPO. Here’s how the valuation works out:

It’s important to remember that this valuation reflects the total amount of shares outstanding. The MHC owned 53% of these shares. In a few years time, the MHC would likely sell off its shares. At this point, cash would be added to the balance sheet, but minority holders would not be diluted.

The deli man figured that in the future the MHC would sell its shares. Maybe they’d sell at 90% of book value. Here’s how the math would work out.

So if the second step conversion happened at 90% of book, buyers in August 1999 would be purchasing at 68% of proforma book value. A cheap price. Now maybe the conversion wouldn’t happen at 90% of book. Or maybe the conversion would never happen and management would keep the MHC in limbo. On the other hand, book value would likely be greater in the future as retained earnings would increase with each passing year. Meaning second step proceeds would be greater since book value would be higher.

Bank Metrics

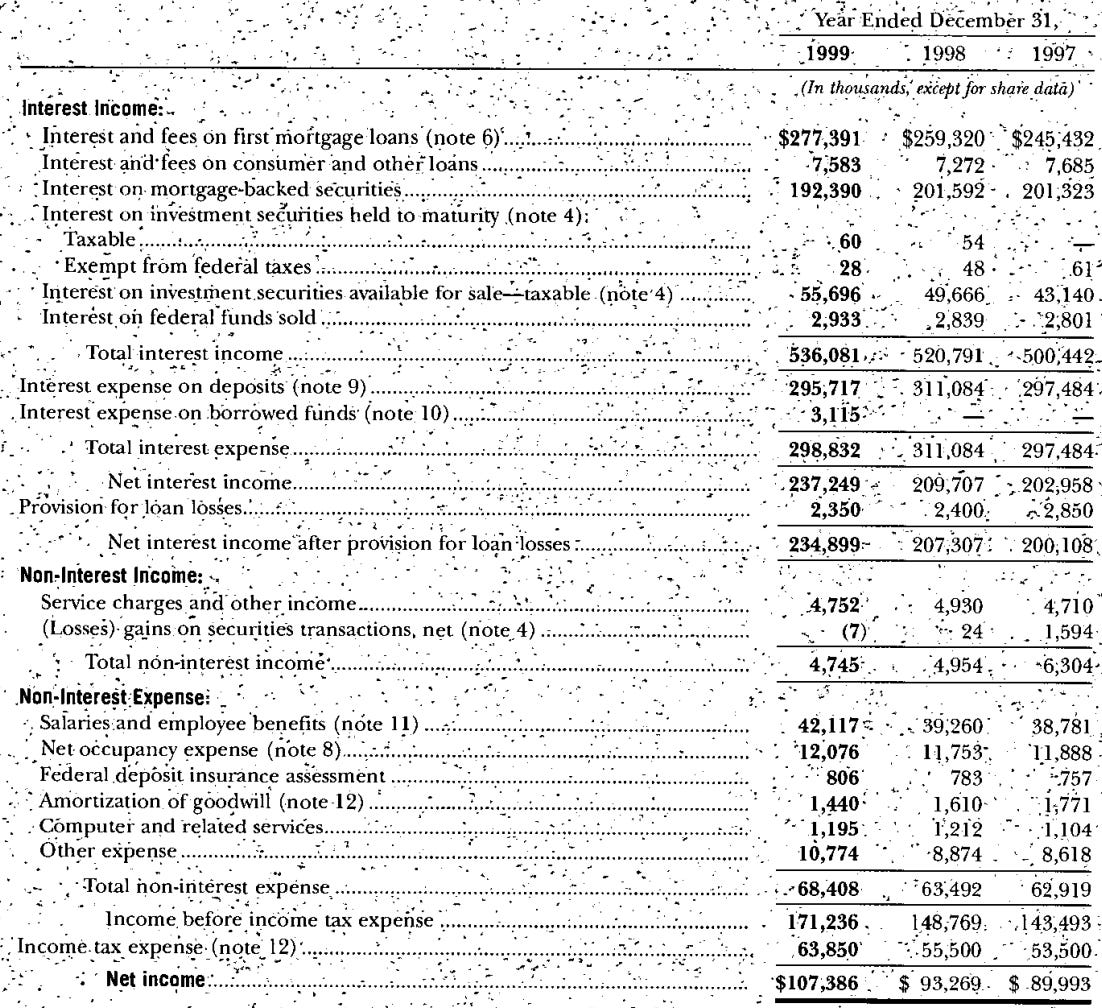

So the bank was cheap on a proforma P/B. And this capital structure would be a bit difficult for investors to understand. But what about the bank itself? Well, Hudson City was a good business. Here’s a few snapshots from the 1999 annual report.

ROE and ROA were strong.

ROE had been in the double digit range each year from 1995 (the earliest data point presented in the annual report). The dip to 9.05% in 1999 was caused by the influx of capital from the IPO that had not been fully deployed by year end.

Net income was increasing each year. IPO capital could be used to boost earnings in the following years.

Net interest income growth was far outpacing increases in non-interest expenses.

Hudson City had a strong efficiency ratio for each year presented.

Financial Statements

Balance Sheet

Income Statement

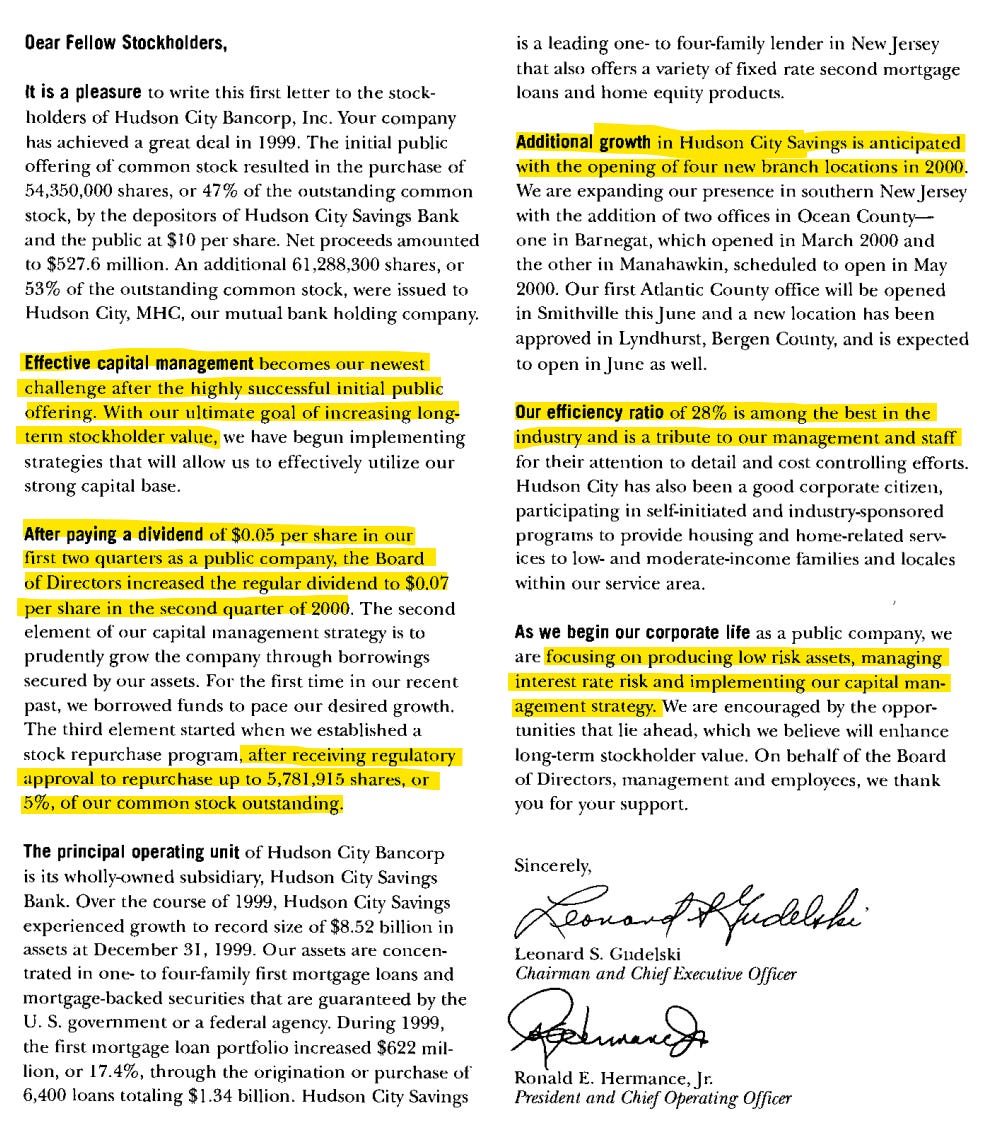

Management Commentary and Capital Allocation

The bank had grown nicely as a mutual before going public. Equity was growing 12% per year as a mutual. With the added capital from IPO, and a potential second step conversion in coming years, the bank had a long runway of capital to deploy. If it could continue earning high returns on equity on incremental capital, returns could get very interesting. And remember, public market buyers in August 1999 were getting this bank at 68% of proforma book value.

Management was doing the right thing with capital, too. Management stated that they intended to do the following:

Buy back 5% of the outstanding stock annually

Issue increasing dividends annually

Grow organically by expanding the branch network

Make acquisitions

The CEO’s letter in the annual report is a thing of beauty:

It’s interesting, because the bank had proven itself to be a good business. Management had held true to their word. Now they had additional firepower to grow per share value. Yet the business traded at a steep discount to intrinsic value. The investing world was simply disenchanted with banks. It reminds me of the landscape we experienced through the back half of 2023 after the SVB meltdown. Many bank stocks were crushed, even those that didn’t deserve it.

How It Worked Out

In the four years following the IPO, the stock increased 829%. Profits continued to grow. In 2003 Hudson City earned $207MM. Both Greenblatt and the deli man made a nice profit.

Joel Greenblatt told the story of Hudson City when asked “what’s your best investment ever”? The stock compounded at 60% a year for 4.5 years. Greenblatt may have had greater IRR’s in his investing career but he names Hudson City when asked the question. I think he mentions it because of all that unfolded after finding the deli man.

If it weren’t for the deli man posting on a Yahoo message board, Greenblatt wouldn’t have been inspired to start VIC. And a lot of great things came out of VIC - especially for Greenblatt. We know he funded Michael Burry and Norbert Lou because of their writings on and off the platform. I’d bet there are others that aren’t known publicly.

The moral of the story is that alpha can come from anywhere. I like the Hudson City case study, but I love what it led to.

Thanks to Joel Greenblatt for starting VIC, a place where some of the best investing pitches have been memorialized. And thanks to the deli man - the first domino that started it all.

DISCLOSURE: NOT INVESTMENT ADVICE. I MAY OWN SOME OF THE SECURITIES MENTIONED IN THIS ARTICLE. I MAY BUY OR SELL AT ANY TIME. THIS IS THE INTERNET AND YOU’RE LISTENING TO A GUY NAMED DIRT.

I was watching the newest interview from We Study Billionaires where Bob Robotti speaks of the demutualization process for Leucadia and the gains he made there. Wouldn’t have understood it without this article - thanks Dirt!

I wonder what your (or my) Hudson Bay may be. Let's circle back in 2044. Till then, will stay tuned in...