If I could invest in only one strategy for the rest of my life, it would be net-nets.

It’s the most durable, time-tested strategy to outperform the index.

Ben Graham, Warren Buffett and Joel Greenblatt all found success in net-nets.

I don’t have the exact data on my net-net performance over time, but I’m confident that it’s returned more than 20% per year.

What Is a Net-Net?

If you’re reading this article, you probably know what a net-net is, but just to refresh, here’s how it works:

A net-net is a stock where net current asset value (NCAV) exceeds market cap.

Net current asset value = Cash + Accounts Receivable + Inventory - Total Liabilities

In short, NCAV is a proxy for liquidation value. Imagine a company collected all its receivables, and sold its inventories, then paid all its liabilities and shut down the business. The remaining sum would be leftover to distribute to shareholders.

In order for a stock to be a net-net, NCAV must exceed the current market cap. In other words, the stock is valued as if it were worth more dead than alive.

Why Does It Work?

Most businesses won’t have an NCAV greater than $0. And this makes sense. Think about it - current assets are the things a business owns that will convert to cash within a year. Total liabilities are the total claims a business owes - those due in the next year and far beyond.

Consider a company that owns a mortgaged property. In our NCAV calculation, the property will receive zero asset value (because the property is not a current asset). Yet the mortgage will be counted, because it’s included in total liabilities.

So to even achieve a NCAV greater than $0 is unattainable for most modern businesses.

Now, to achieve an NCAV that is not only positive, but greater than the current market cap is very rare.

So why do net-nets work? Because, by definition, they are incredibly cheap.

Not So Fast My Friend

Now, success in net-net investing isn’t as simple as running a screen and buying every net-net that appears. In fact, that may be a great strategy to incinerate capital.

As it turns out, the market is pretty smart, and generally efficient.

Most net-nets trade “as if they were worth more dead than alive” because the value of being “alive” will dwindle with each passing quarter. Most net-nets lose money, and by definition their assets decrease and/or their liabilities increase. So that apparent net-net is illusory. The equation will soon flip, or the business will soon fail.

If we sample 100 net-nets my guess is the business profiles will look something like this:

75 companies will be some kind of busted pharma/biotech/hopeless business endeavor that raised a bunch of cash and is hemorrhaging that cash by the day. They’re currently net-nets, but the current asset balance (generally cash) will dwindle as the company continues to pursue its vision. Avoid these like the plague.

15 companies will be net-nets that historically break even and have ~zero cash. They’ll be heavy on niche inventory that is worth drastically less in anyone else’s hands. Imagine a company that manufactures windows for homes. They make money sometimes; they lose money sometimes. Their net-net value is driven by a massive slug of inventory. The problem is most of this inventory is raw glass, adhesives and component parts. The inventory only has reasonable value to the extent it is turned into a finished good. And that will take lots of time, money and effort to complete. Avoid these businesses.

7 companies will be net-nets because the numbers are wrong. The screen shows a net-net but the stock traded down 40% in the last 3 weeks. There was some giant, unpredicted interruption in the business. The oil wells ran dry, the factory was flooded, a product was recalled, a large lawsuit was filed/lost. Obviously, stay away from these.

3 companies will be historically profitable business sitting on net cash. They’ll make some simple product and will have been in business for 50 years. 46 of those years will have been profitable. The company won’t be talking much or doing anything interesting. If you read the message boards, there will be a bunch of people complaining that the business doesn’t pay a dividend or buy back stock. They’ll call the company a value trap. In general, sentiment will be bad. Not because people think the business will fail, but because they don’t believe the stock will go up anytime soon. This is where you want to focus.

Net-Net Criteria

Here’s my criteria for an investable net-net:

Sustainable, understandable business model: Ideally, I want a business that has been around for at least 20 years. I need a business that I can understand. Something you could explain to granny. If the business description is something like “optimizing B2B connections through proprietary system integration solutions”, I’ll be taking my capital elsewhere. If the business manufactures mailboxes, well that’s a little more understandable.

Low or no debt: Debt is leverage. Leverage magnifies outcomes. Good outcomes are made great, and bad outcomes are made terrible. Given that a net-net is incredibly cheap by definition, any re-rating toward a more reasonable valuation will result in a great outcome. We don’t need leverage. So why introduce it? I like my return without additional risk.

Consistently profitable business: We want a business that earns a profit the vast majority of the time. Ideally, I’d like a business that has generated an operating profit for each of the last 10 years. Additionally, I want a business with positive retained earnings.

Strong cash position: I like my net-nets to be heavier on cash than A/R or inventory. Cash is the easiest of the three to value. A/R can go unpaid, and inventory can become obsolete or require significant investment to sell. A strong cash position also provides optionality. All kinds of good things can come from having ample cash on hand.

Honest/reasonable management team: All the above criteria are great. But if management are crooks or idiots, it won’t matter much. The good thing is sleepy companies with simple, profitable businesses and minimal debt don’t tend to be run by crooks. You’ll know it when you see it. Companies that issue shares or consistently branch into new business lines (and fail) are pretty easy to spot. Importantly, I’m not saying management needs to be excellent at allocating capital. We just need them to preserve it. They don’t even have to be good. “No capital allocation” is better than “bad capital allocation”. We can still make money with “no capital allocation”, provided the price is right.

Fictional Example

Let’s make up a company: we’ll call it Wesvac, Inc. Wesvac is a 70-year-old business that manufactures and distributes hot water heaters, dishwashers and other household water-related component parts.

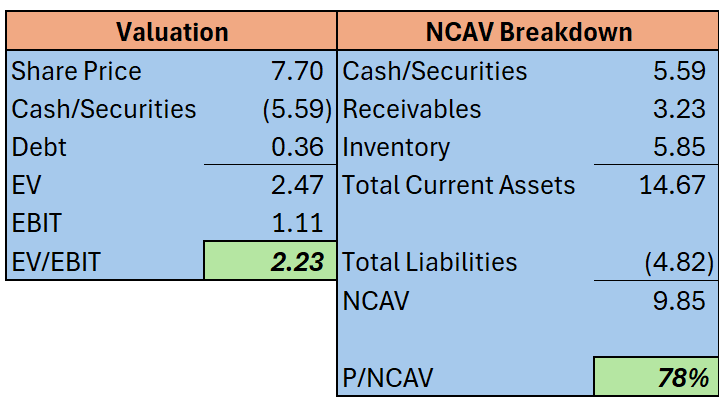

Here’s a quick peak at the company’s valuation:

Wesvac trades at 78% of NCAV and only 2.23x EV/EBIT.

Here’s a few more notes:

Wesvac has generated positive EBIT for each of the last 20 years.

Wesvac revenue has grown at a 2.8% CAGR over the last 15 years. That’s not great, but it reflects growth in line with inflation.

The CEO and his family have been involved in the business for 40+ years. They successfully spun out a large portion of the business in the early 2000’s, generating substantial value for shareholders.

The CEO owns more than 50% of the outstanding shares.

Wesvac doesn’t provide guidance, they just give you the numbers each quarter with little comment.

Retained earnings are twice as large as the current stock price.

So what can we glean from this information?

Wesvac is cheap, profitable and sitting on a mountain of cash. It doesn’t appear management will quickly deploy that cash, but they aren’t blowing it on crazy growth projects either.

Wesvac has been around for a long time. The business withstood new competition entering the market.

Return on equity isn’t great, and it’s getting worse by the year as the business retains cash. Return on equity could become great overnight, if a large dividend or buyback occurred. But this isn’t likely to happen.

Here’s the kicker - Wesvac isn’t a fictional company. It’s a real business. I wrote about it here:

I changed the name, and slightly altered the industry. The per share numbers are adjusted to mask the business, but the valuation metrics are accurate as of the April share price.

“Wesvac” is an illiquid security. And the share price has increased 30% since I originally discussed it in April. Shares are up 50% in the last 12 months.

But this is what happens when you own cheap, profitable, sustainable net-nets. Folks on Twitter and other message boards will complain about the lack of action by management.

They’ll say things like “well this business deserves to trade at a discount, it isn’t unlocking value”.

And I agree. Net-nets aren’t generally great businesses. But the value implied is still too low. I’m not saying these businesses should trade at 20x. I’m saying they should trade for more than “liquidation value”.

The price drifts down for years and folks get dejected. They can’t take the pain. This brings me to my next point.

Buy, Hold, Sell Strategy

I hear you reader, you’re saying “How long should I hold my net-net? It’s been 2 years and the price hasn’t moved”.

Here’s the strategy I’ve adopted over time:

Identify net-nets that meet my criteria.

Buy stock.

Hold for 1 year.

Revisit thesis. Does the business and management still meet my net-net criteria?

If stock is still a net-net, hold.

If stock is no longer a net-net, sell.

I altered my holding strategy over the years. I used to sell the moment a stock failed to be a net-net, regardless of how long I owned the shares. But I found that I would often sell too early. You see, when you’re buying at such depressed prices, the upside can be far greater than your initial purchase.

I now endeavor to hold my net-net’s for at least a year. I don’t want to sell before the 1-year mark, regardless of price movement.

I listened a Focused Compounding episode 4 years ago that helped me refine my strategy. Everyone should listen to this. Geoff Gannon is one of the clearest thinkers I’ve encountered in investing:

Net-Nets - Focused Compounding Podcast

Closing Thoughts

In my experience, the best performing net-nets are illiquid and unknown. I like stocks that are too weird, or too illiquid to be owned by institutions.

I think of valuation as if it were a bell curve. Large, well-covered companies are likely to be near the middle of the curve. They have the most eyeballs/analysts. Some far flung, $65MM market cap business in Lincoln, Nebraska is likely to have zero analyst coverage. It can be 3 or 4 standard deviations away from the center. This is where I want to play.

I doubt an investor could build a high return, adequately diversified net-net portfolio in a day or a week. My strategy is to look at companies all day long. For every 1,000 publicly traded businesses, there may be 1 or 2 net-nets that I’ll want to own. When I find them, I simply add them to the portfolio.

With the market at all-time highs, it can be difficult to find cheap, sustainable net-nets. But I promise they’re out there. It just takes work to find them.

DISCLOSURE: THIS IS NOT INVESTMENT ADVICE. I MAY OWN THESE SECURITIES. I MAY BUY OR SELL THESE OR ANY OTHER SECURITIES AT ANY TIME. I MAY NOT TELL YOU IF AND WHEN I BUY OR SELL. THESE STOCKS MAY BE ILLIQUID AND YOU SHOULD UNDERSTAND THE IMPLICATIONS OF THAT IF YOU BUY THEM. THIS IS NOT TAX, LEGAL OR FINANCIAL ADVICE. I AM NOT YOUR FIDUCIARY. THIS IS THE INTERNET AND YOU’RE LISTENING TO A GUY NAMED DIRT.

This is a masterpiece. It's one of those things I will read over and over until it's ingrained in my mind.

I think I have stumbled onto the same conclusion. I recently backtested Graham's net-net strategy for 20 years on nasdaq and nyse. A huge majority of these are un-investible and should not be bought as a basket. After looking at 605 investments, 28 were quality enough to invest in without hindsight bias. Which is close to your 3% estimate. https://benevolusinsights.com/2025/02/12/us-public-equity-research-backtesting-ben-grahams-net-net-investment-strategy-in-us-markets-from-2004-2024/