Warren Buffett Case Study: Studebaker 1965

How Buffett doubled his money in 12 months. Buying a cash flowing, debt free basket of hidden assets.

In 1999 Warren Buffett claimed he could earn 50% a year if he were managing $1 million. People often discuss how Buffett had it easy in the 1950’s and 1960’s. Markets were less efficient.

But there is a less discussed Buffett quote. He doubled down on this claim at the 2012 Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting. A questioner asks Buffett about his 50% per year statement. The questioner wonders if Buffett could do even better than 50% per year if he was given $1 million today (2012).

Buffett states the following: “… have we learned things in managing since we were at that level where we could do even better with $1 million now than we could have done with $1 million then? And I would say the answer to that is yes.”

That’s crazy. Buffett says he could do better with $1 million in 2012, than he could in the 1950’s. In the 1950’s he was compounding well above 50% annually.

Here is a link to Buffett’s discussion at the 2012 annual meeting. Go to the 1:39:35 mark of the afternoon session for Buffett’s comments on this topic:

Buffett Can Earn Better Than 50% on $1 Million

Today’s Opportunity Set

I believe an investor today with $1 million has the same opportunity set as Buffett in 1955. I arrived at this conclusion after spending thousands of hours looking at tiny companies. There are ridiculously mispriced securities for small investors to buy. The problem is you have to find them on your own. Nobody will tell you about them. Here’s an interesting example that young Buffett found in the 1960’s.

Studebaker – The Setup

Warren Buffett and David “Sandy” Gottesman met in 1962. They were in the same line of work and had an affinity for similar securities - mispriced, boring, old-line businesses. One such company presented itself in 1965. Studebaker, the famed automobile manufacturer, was exiting the car business. Its heyday was long gone, and the auto division had recorded losses for five consecutive years leading up to 1963.

Studebaker had a saving grace though. It had diversified its business throughout the years. By 1963 there were 13 different business units. While Studebaker was mostly known for its cars, there were a whole slew of other assets inside the business. Chemical compounds, floor cleaning machinery, generator manufacturing, tractor manufacturing, commercial refrigeration and several other industries were represented inside the Studebaker brand.

Gottesman – Hot On The Trail

Gottesman kept his ear to the ground on all things cheap. He knew there was potential for great value inside Studebaker. He also knew that there was a huge tax loss that would protect future profits from federal income tax. Here’s how Gottesman explains the situation:

Notes from 1963 Annual Report

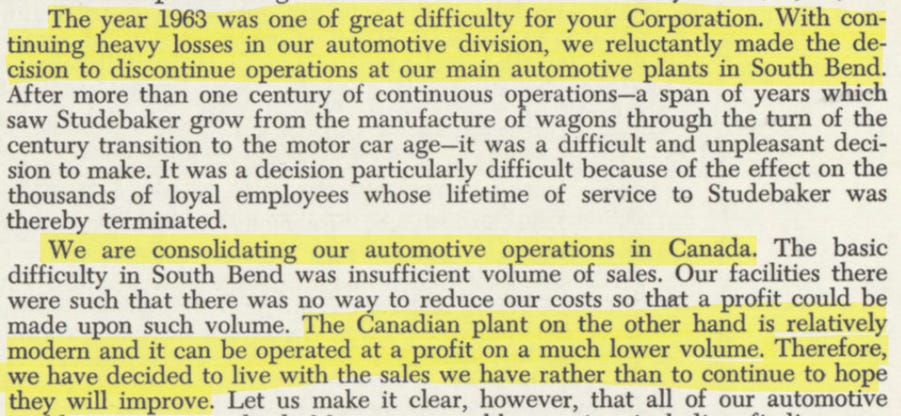

Studebaker hired a new management team in 1963. The intention of new management was to return the company to profitability by shedding bad product lines. Let’s take a look at a couple quotes from the 1963 shareholder letter (the first for the new President and Chairman):

Management knew the auto division was the problem. Shutting down the flagship plant in South Bend, IN would have been a huge pill to swallow – but the new team did it. They knew where profits were coming from. Management was accepting reality as it was. There were no discussions of heroics – just a sober–minded focus on profits.

Buffett and Gottesman would have known that the other entities aside from auto were profitable in 1963. Management also says losses are behind the company. Leadership had an optimistic feel for the business as they worked into 1964.

Notes from 1964 Annual Report

Sales shrank dramatically in 1964, as the Company significantly reduced its auto manufacturing capacity. All manufacturing was moved out of Indiana and into Canada. Total auto production dropped from 90,000 units in 1963, to 20,000 units in 1964. Studebaker was clearly committed to this path of profitability.

Debt reduction was happening rapidly. The cash generated for debt paydown was largely coming from the sale of the Indiana facilities.

Studebaker was well capitalized amid the operational shift. Current assets were considerably greater than current liabilities and nearly exceeded the balance of total liabilities.

There was ample cash offsetting debt. None of the debt was short term. There was very little liquidity or solvency risk.

Working capital was quickly decreasing.

Again, let’s look at a few quotes from the shareholder letter in 1964:

Studebaker produced 20,000 units in 1964. This was its break-even point. No reaching, no reneging on the vision. The Company was definitively telling its dealer network that production will only last if the business can earn a satisfactory ROI.

Management kept shedding assets. By February 1965, debt was down to $18.4MM.

Valuation

New management created a ton of value in its first two years on the job. Buffett and Gottesman began buying the stock in 1965. According to Gottesman they paid $18-20/share. For our purposes, let’s assume that the pair paid $19/share.

There were 2.78MM shares outstanding at year end 1964 (some sources will quote a higher share count, there was a reverse split in early 1965. Gottesman is quoting post-split shares). Given effect for the convertible preferred classes and stock options, the fully diluted share count was 2.96MM. This gives us a market cap of $56MM at $19/share.

As of February 1965, debt was reduced to $18.4MM. This compares to $14.3MM of cash and securities at year end 1964. Call it $4MM of net debt. So we have an enterprise value of $60MM. This compares to $8.1MM of net income. So, on a trailing basis, Buffett and Gottesman were buying shares for ~7x earnings.

Due Diligence

7x earnings is a cheap price. But there was potentially greater earning power to be achieved. Afterall, management was only two years into cleaning up this gigantic mess. There were likely additional savings on the auto front. Reinvestment in profitable brands could lead to even greater profits. Additionally, management may have had more assets to shed. This could result in additional cash being shaken loose for further debt paydown and/or dividends/buybacks. Let’s have another look at Gottesman’s comments on the deal.

STP

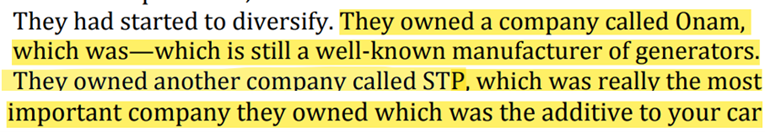

Studebaker purchased STP in 1961. That year STP did $6MM of revenue. In 1962, revenues grew 37%, to $8.2MM. We don’t have exact numbers for 1963, but management states that sales volume grew 15%. If there were price increases, revenue may have grown 20%+ in 1963. After 1963, there are no concrete numbers presented in the annual report for the STP segment.

While there was little information provided by the company, Buffett and Gottesman would have known that the product was quickly gaining popularity throughout the United States. In the 1964 Indy 500 auto race, two thirds of drivers had STP additives in their car. Management notes in the 1964 annual report that STP had become the sales leader among oil additives in the U.S.

So, Buffett and Gottesman knew that STP had great potential, but management stopped giving performance numbers. Buffett would not be deterred. Here’s another quote from Gottesman:

Buffett sends someone out to pull intel on the factory by monitoring rail cars. Keep in mind, at this point STP represented ~4% of the overall revenue of Studebaker. Buffett had guys out there doing diligence on some piece of the business that would seem completely trivial at the time. And this was a business where the inflation adjusted market cap would be ~$600MM today. This was not some giant company.

As it turned out, Buffett and Gottesman were right about STP. It was a crown jewel. In 1968 Studebaker spun off the business. This is what the STP financials looked like at the time.

Sales grew rapidly. Note the 19% ROE. STP had ~$15MM of excess cash in the business from the public offering. If we remove excess cash, and reduce equity to ~16MM, ROE jumps to 37%. This was a very good business.

When Studebaker took STP public in 1968, there were 5.67MM shares outstanding valued at $23.60/share. At the time STP went public its business was valued at $134MM! Buffett and Gottesman got their original shares of Studebaker, which owned STP and a whole slew of other profitable assets, for just $56MM.

Onan

Onan was a strong business too. Onan produced $15.5MM of revenue in 1961. 1962 sales totaled $18.9MM and 1963 sales were $20MM. Onan would go on to grow nicely. The subsidiary was spun out of Studebaker in 1970 when it was doing $56MM of revenue and ~$8MM of pretax profit. I don’t have good data on exactly how profitable that division was in 1965, but let’s assume it was doing similar pretax margins to 1970. Let’s say Onan was clipping ~$3MM of pretax profit when Buffett and Gottesman bought their stake. Onan was acquired by Cummins in 1986 and is still around today.

Putting It All Together

Buffett is well known for using publicly available information better than almost anyone else. His entire career has been built on distilling the salient points. In the case of Studebaker, I think it would have been difficult to buy into such a historically lousy business. But by the time Buffett showed up in 1965, the business had already taken steps to put its money where its mouth was. Studebaker was saying the right things, and the financials reflected how serious the management team was about the turnaround.

By the time Buffett and Gottesman began buying stock the business was basically debt free and earning a nice profit. They probably knew there was additional gas in the tank. If we knew what Buffett knew, we’d likely take the same bet. It’s interesting, because in small companies today you can get the same information edge by pulling public data or doing research that nobody is willing to do.

Buffett and Gottesman saw a stock that was very likely undervalued. They listened to what management said, and when management proved to be true to its word, the pair bought the stock. It’s worth noting that they bought shares after management had substantially completed the turnaround and de-risked the business. I think this is key. Find things that are cheap and safe now. Betting on the future is hard. Seeing the present clearly is much, much easier. I want to buy only when it’s plainly obvious that a stock is cheap, profitable, and reasonably durable.

I’m reminded of Buffett’s investment in PetroChina in the early 2000’s. He said the company was worth $100 billion based on earning power and a conservative estimate of oil in the ground. Yet the stock was trading for $35 billion, or 3x earnings. Management had written in its annual report that the company would be paying half the profits out as a dividend. So Buffett was clipping a 16.7% yield from the outset. He bought when shares were cheap and capital allocation was clear.

The other piece of this case study I find so interesting – Buffett knew that STP was the crown jewel. I’m guessing he thought the business had great potential. But STP was so tiny at the time. I wonder if he grasped the economic power that came with engine additives. In 2011, Buffett would buy Lubrizol for nearly $10 billion. Pat Dorsey said part of what made Lubrizol a good business was that its product was a small component of the overall machine cost, yet integral to the process. The lubricants used in a large bulldozer are just a tiny piece of the overall cost, but if those lubricants keep that dozer running safely and efficiently, a lot of value is created for the dozer’s owner. Maybe Buffett saw that with engine additives in the 1960’s. I don’t know. It’s odd that they did so much work on such a small piece of the business. But he was obviously right to dig so deep.

Getting Paid

Buffett and Gottesman bought the majority of their shares below $20. How they went on to sell that stake is pretty funny. I’ll let Gottesman tell it:

There you have it. Buffett and Gottesman more than doubled their money on the original stake they purchased. Then through a combination of keeping an ear to the ground and acting quickly, they were able to make a cool 26%+ (at least) on the stock they grabbed up to $35.

Buffett and Gottesman sold their shares sometime in 1966. So they likely owned the shares for around a year. Studebaker earned $10.7MM of pretax profit in 1965 and $16.5MM of pretax profit in 1966.

Gottesman and Buffett remained lifelong friends. Gottesman served on the Berkshire Hathaway board from 2004 until his death in 2022. His stake in Berkshire was reported to be worth $2.6 billion at his time of passing.

Disclosure: This is not investment advice. I’m not your advisor. I’m not your fiduciary. Do your own diligence. This is the internet and you’re reading content from a guy called Dirt.